Boaters and fishermen in the Atlantic Ocean should be vigilant this winter for North Atlantic right whales, particularly in state and federal waters along the coastline of Sebastian and Vero Beach until April. These whales are frequently spotted at Sebastian Inlet during winter months.

This endangered species, with an estimated population of just 360, is notoriously difficult to spot. Vessel collisions not only pose a danger to passengers and crew but also threaten the survival of these whales.

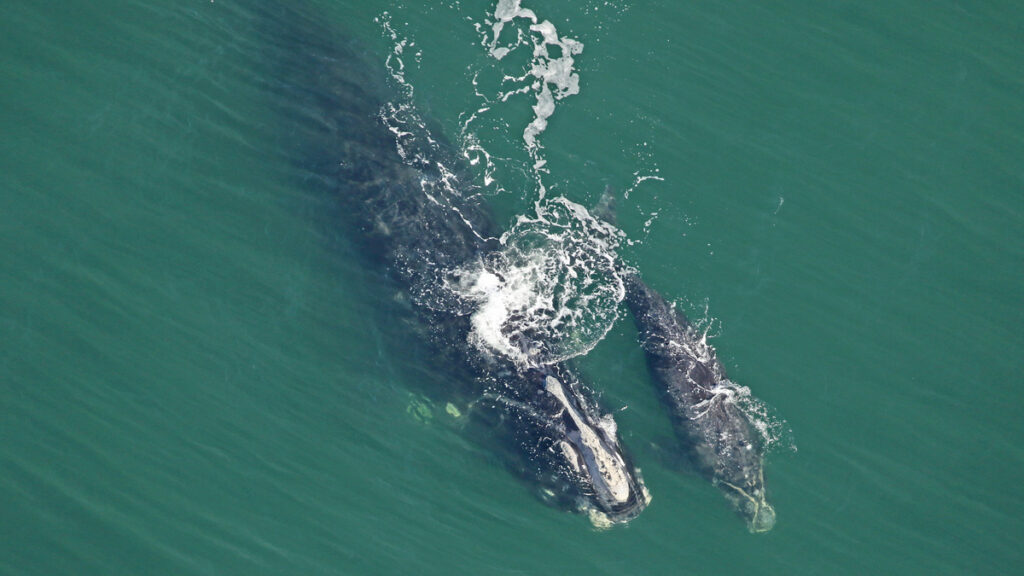

The season’s first mother-calf pair was observed near South Carolina on November 28. Since November 15, several adult females have been seen from North Carolina to Georgia, indicating potential calving this winter. Aerial surveys will intensify around Florida and Georgia in December.

To ensure safety during right whale season, boaters should:

- Navigate slowly to allow time for reaction.

- Maintain a vigilant lookout for signs like black objects, white water patterns, and splashes.

- Avoid boating in darkness, poor visibility, or rough seas.

- Use resources like WhaleMap.org or the Whale Alert app for updates on right whale movements.

- Heed local marina or boat ramp signage for guidance on spotting and reporting right whales.

- If a whale is sighted, reduce speed or stop, assess the situation, and cautiously exit the area without following the whale. Maintain a minimum distance of 500 yards from right whales, as required by law.

- Report any whale sightings or collisions to the U.S. Coast Guard via marine VHF Ch. 16 or at 1-877-WHALE-HELP (942-5343).

Since 2017, these whales have been experiencing an unusual mortality event, encompassing a variety of conditions from non-lethal injuries and illnesses to severe injuries and deaths. This event has affected over 20% of the population, a significant number for an endangered species already struggling with declining birth rates. Research indicates that only about one-third of right whale fatalities are recorded.

North Atlantic right whales are easily recognizable by their robust, black bodies without dorsal fins and distinct “V-shaped” blow spouts. Their tails are wide, deeply notched, and entirely black with smooth edges. Some have black bellies, while others feature irregular white patches. Their short, broad, paddle-like pectoral flippers are notable. Calves measure around 14 feet at birth, with adults growing up to 52 feet.

Uniquely, these whales have rough, white patches of skin on their heads, known as callosities, which appear white due to whale lice. These callosities are unique to each whale and are crucial for scientists to identify and track population size and health. Aerial, ship-based surveys and the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium’s photo-identification database, maintained by the New England Aquarium, are instrumental in this tracking.

Right whales are often seen breaching or swimming above water with their rostrums as they skim-feed on plankton. They feed by swimming through dense patches of copepods and other zooplankton, trapping these organisms in their baleen. They feed throughout the water column, from surface to bottom.

Groups, known as surface-active groups (SAGs), are observed year-round in all habitats, where right whales engage in socializing and mating. They communicate using low-frequency sounds for various social interactions.

The whales are primarily found in the Atlantic coastal waters along the continental shelf, sometimes venturing into deep offshore waters.

They migrate seasonally, often alone or in small groups. In spring, summer, and fall, they are typically in the waters off the coast of New England and Canada for feeding and mating. In the fall, some travel over 1,000 miles to the shallow coastal waters off South Carolina, Georgia, and northeastern Florida for calving, though migration patterns can vary.

Right whales are believed to live at least 70 years, but determining their average lifespan is challenging due to relatively recent scientific monitoring. Post-mortem age estimation in right whales is possible through ear wax analysis. Comparative studies with closely related species suggest that some might live over 100 years. However, current lifespans for North Atlantic right whales are shorter, with females living around 45 years and males about 65 years, primarily due to human-related causes rather than natural aging.

Recent research shows a higher mortality rate in adult female right whales compared to males, resulting in a skewed population with more males. This imbalance is growing over time. Females, especially those under reproductive stress, appear more vulnerable to chronic injuries from entanglements or vessel strikes.

Female right whales reach sexual maturity around 10 years of age and typically give birth to a single calf following a year-long pregnancy. A healthy interbirth interval is about three years, but currently, females are having calves every 6 to 10 years. Biologists attribute this reduced calving frequency partly to the added stress of entanglement.